Ahoy there hungry sailor 👋

Ah, ze provisioning! It is like preparing for a grand feast! One that is 2 to 3 week long though, if you are crossing the Atlantic 😬. You need to commit, because where you’re going (the middle of the ocean) there are no supermarkets nearby.

Maybe that sounds like a daunting task? You might be hearing a little voice in your head asking a thousand questions:

- What do folks like and how do I keep them happy?

- Does my crew have any allergies?

- How do I handle the logistics of buying dozens of kilograms of food?

- What about storage and refrigeration?

- Who cooks during the passage? Do we have a role for that? Or does everyone share the responsibility?

We asked ourselves all these questions and more. To help structure today’s discussion, we have divided this post into the following sections:

- ⛑️ Food safety

- 🧮 Preparations

- 😱 Shopping

- 🍋 Storing

- 🍝 Meals onboard

⛑️ Food Safety#

If you go to any travel medicine consultation, you will hear the golden old adage countless times: “when travelling to tropical countries, you boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it”.

We followed this motto quite closely, for two reasons:

- With all the preparations that went into this trip, we did not want us or the crew going through a potentially troublesome infectious disease just before the crossing.

- Better yet, we wanted to make sure no one got sick whilst we were at sea, where we would inevitably be isolated and limited in resources (although we did invest quite a bit of time into our medical kit… but more on this in an upcoming post!)

In practice, this meant that we, for instance:

- Peeled our carrots and cucumbers 🥕🥒

- Did not buy pre-chopped fruits and veggies 🔪

- Parted with lettuce for the whole of the crossing 🥬

- And did not eat raw fish or meat 🐠 … among other things.

🧮 Preparations - How do I know what I need?#

To calculate what we would need to buy, we created a Google Sheets (see sample here).

Let’s look at it step by step.

The first tab is very simple and was reserved for assumptions and fixed variables. For instance:

- Fixed variables

- How much water can the tank(s) hold?

- How many meals per day will we cook?

- Assumptions :

- How much water should an average person consume per day?

- How many litres of water do we expect to expend in cooking?

- How many grams of protein, carbs (pasta, rice etc) and veggies should we allocate per person, per meal?

- How much cereal, dairy and fruit should we plan for each person, per day?

In the second tab, we proceed to first list the variables for that trip:

- How many people will we have onboard?

- How many nautical miles do we think we will cover?

- What average speed do we think we will do?

- Based on this information, how many days do we think the passage will take?

- Finally, account for delays: we added a 20% buffer to our first estimate.

Based on these variables and those from the first tab, we can then calculate the number of total meals, as well as how many kilos we would need to provision for each category. These categories were:

- Carbs

- Fruit

- Milk/yoghurt

- Oats/cereal

- Protein

- Snacks

- Veggies

- Other

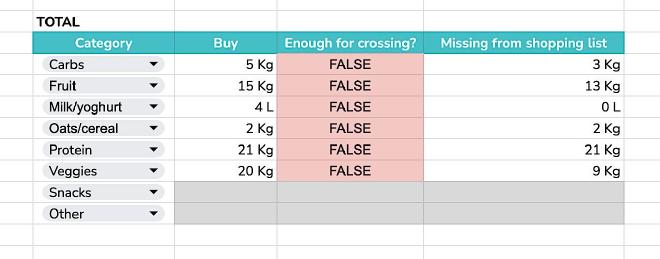

Combining this information with an inventory (third tab) using these same categories, we can then estimate how much (in kilos/liters) of each category we needed to buy.

With this done, generating the shopping list (fourth tab) was the easy part. Each item was put into a category and (drumroll please 🥁) the spreadsheet, based on the inventory and shopping list, tells you how much more is needed in each category in order to hit the quantities needed for the crossing.

Have a go! Open up the spreadsheet, create a duplicate and play around with the quantities in the inventory and shopping list and see if you can get the summary table (see here and scroll down to view it) to list “True” instead of “False”.

This approach made shopping very flexible 👌 because, as long as we met the category goals, we could shop whatever we wanted and we knew we would have enough food to feed the crew.

Have a look at the spreadsheet yourself! If you end up using it, please do mention this blog post and tag us. It’s important for us to know if the resources we are sharing are useful. 😉

Creating the spreadsheet was, however, only the first step. Inês created the spreadsheet and then exchanged thoughts with David, to make sure nothing obvious was missing. We then proceeded to invite our very international crew to come up with recipes they would like to cook during the passage. Several people contributed, and the ingredients needed were taken into account into the shopping list.

😱 The dreaded shopping#

Next came shopping. For this, we did multiple round to the HyperDino supermarket in Las Palmas. We did most of our provisioning in Las Palmas, since we knew Gran Canaria would offer more options (and quantity) than Mindelo. All the dried and canned goods were bought in Las Palmas, as well as the fruit and veggies needed for Leg 1 (Gran Canaria → São Vicente). We then stocked up on fresh produce in Cape Verde (shoutout to the municipal market of Mindelo, in particular to Anderson and his mother, who tirelessly went through our lenghty shopping list with us ❤️). In retrospect, we could have used some delivery services or rented a car, but instead took two big carts and did multiple rounds of shopping by foot. It was all right, in the end, and we got some steps in towards our daily goal 👟.

🍋 Storing#

We read up quite a bit on this topic (mostly here), to make sure that food would not spoil. We used fruit nets for storage and respected certain rules, such as keeping bananas 🍌 away from the rest of the fruit. However, we also deviated from recommendations sometimes. For instance, Inês refused to waste aluminium foil on carrots (I really do not like to produce waste!). Instead, we peeled the carrots, cut them in round slices or sticks and either froze them or placed the sticks in a container with water in the fridge (tip courtesy of one of our crew members), to keep them crisp for snacking. In addition, to avoid carrying any bugs onboard, we washed the fruit and veggies on the dock and let them dry fully on the cockpit table before storing them.

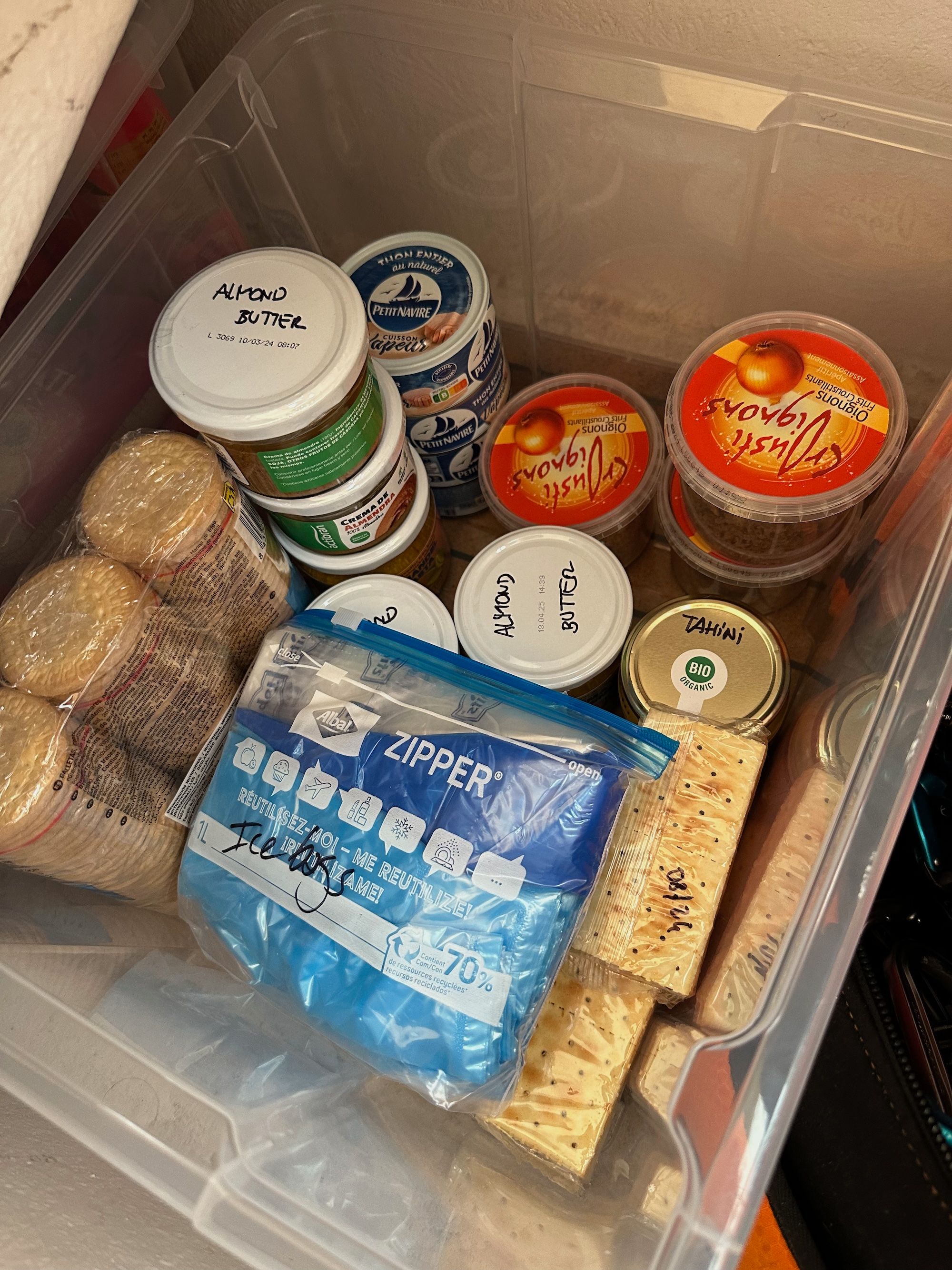

When it came to storing dry foods, we thought about the user experience we would want for ourselves. What do I mean with this? Well, you should strive to make your future self’s life easier. For instance, we wanted to make items easy to find even if we forgot their exact placement. Thus, we stored food in large plastic boxes organised according to categories of food (pasta, rice, legumes, protein, snacks). Since we also look down at our locker and bilges, we labeled certain items with a Sharpie, to make them easily recognizable when spotted from above. Also think about ways to save space: one way to do so (and to apparently avoid cockroaches) is to part with all the cardboard packaging. Take a Sharpie and mark what the product is as well as its expiry date.

🍝 Meals onboard#

All this preparation is an excellent step towards ensuring a great experience onboard but, during the crossing, a lot of work needed to continue to be done. Inês assumed a management or oversight role (depending on the leg) and helped shape consumption patterns. For instance, we had a pretty strict zero waste policy onboard Nuvem Mágica, which served as a good first principle, because this meant that:

- We would cook what we needed (instead of unplanned and potentially excessive amounts);

- We did multiple (and delicious 😋) leftover buffets;

- We did daily rounds of the fruit and veggies, and defined the “fruit/veggie of the day”, which had to be consumed first;

- Based on what needed to be consumed, we adjusted the meal plan.

Then there is the issue of snacking. You want to make everyone feel comfortable while making sure to preserve luxury items such as fresh produce. To this end, we had a snack box everyone could always eat something from. In addition, several crew members added to the snack section of the inventory by shopping their own favorite snacks (olives, dried fruit and dark chocolate were local favourites!).

We wanted folks to be able to eat fresh produce during the whole duration of the trip. And we succeeded! The day before arriving to Grenada, we were eating our last fresh cucumbers. Again, regularly checking our fruit and vegetables and eating them according to ripeness made us naturally eat the more resistant items last. In addition, we mixed in canned goods early on to add in a bit of green to meals without depleting our fresh produce in the first week.

Finally, there was the meal plan. We had multiple recipes we wanted to do during the trip. We cooked some meals ahead (lasagna 🤤) or bought some ready-made food to ensure the first meals of the passage, in case we all suffered sea sickness. After this, we always planned for the following 1-2 days and adjusted based on leftovers and the fruit/veggie of the day. This meant we had a plan, but were flexible 😊 Everyone cooked and was welcome to add in ideas and prepare treats. Some naturally liked cooking a LOT (Camille ❤️), and those that did not cook as much were more involved in cleaning.

In the end, it was quite a bit of work, but we believe it was well worth the effort and made for many great moments on Nuvem Mágica ❤️

📚 Useful resources#

- Our Google Spreadsheet

- The Boat Galley Cookbook

- The ARC Handbook (given out to participants of the World Cruising Club events)